Brian Lewis teaches Bach

This year, the 7th European Suzuki Teachers Exchange Conference in Remscheid, Germany, was delighted to welcome Brian Lewis as their guest teacher and performer. Brian grew up as a Suzuki child himself, the son of renowned Suzuki pedagogue Alice Joy Lewis, and is now committed to growing the legacies of his former teachers Dorothy DeLay and Shinichi Suzuki. In the following video Brian talks about his mother and her words of wisdom about his practice rituals as a young child:

During the course of the conference, which was attended by participants from 21 countries, Brian, who is sought after as a violinist and pedagogue worldwide, shared his charismatic and infectiously enthusiastic nature with the conference participants. Brian hosted a number of workshops, including a three-part masterclass on the Bach Violin Concerto in A Minor, individual masterclasses with students, group classes, and a group session for teachers, before finishing off his visit with the presentation of his solo recital with pianist Heidi Curatolo.

Masterclass on teaching the Bach Concerto in A Minor – 1st Movement:

During the masterclass for teachers, Brian ran a fast-paced and engaging session with lots of demonstrating and trying out of new ideas. Attending teachers were able to play through the repertoire as well as experiment with sound and phrasing concepts.

Phrasing the opening:

Brian encouraged the teachers to consider that there is more than one way to phrase the opening four notes of the concerto. The main consideration is whether to retake the bow, or to leave it on the string. Both scenarios impact the phrasing of this important opening sequence, and would appeal to two equally valid schools of thought.

Brian explained that Suzuki encouraged him to retake the bow as it produced a more consistent sound and bow distribution which is useful when playing the concerto in groups, but Brian’s two Julliard teachers advised him not to retake the bow. Different teachers will always have different, but often equally valid philosophies, and as teachers ourselves, we must consider and understand the implications of any choices we make for our students.

Sound and the Bow hold:

Brian encouraged the class to experiment with their sound by adjusting their bow hold. By moving the bow thumb up so that we put our pinkie on the bottom of the leather, we can replicate a baroque bow hold, which has the advantage of being able to negate the weight of the frog. After experimenting with this hold as a group, the teachers all agreed that it allowed a feeling of freedom with their bowing and sound, which Brian suggested resulted in new possibilities being opened up for phrasing and dynamic choices for the performer.

Brian describes the Bach Concerto in A Minor as the point in the Suzuki repertoire where he encourages his students to play around with the bow hold and the resulting sound differences that occur. This is particularly poignant as he works with his students at this level to develop two important bow strokes valuable in the Bach Concerto in A Minor:

- Bowing with arm weight

- Bowing with release of weight (bow coming to a natural stop, resulting in a resonant Sound)

Both of these bow strokes benefit from the experimentation of sound and bow hold.

Musical Patterns in Bach:

Dorothy DeLay suggested to all her students that they map out patterns in the Bach pieces they were playing. By identifying and analysing the patterns, the student gets to visually see Bach’s architecture, which is an invaluable tool to assist in the interpretation of phrasing and dynamics.

Brian suggests that the analysis of Bach should start with the Bach Concerto in A Minor, as it prepares the student for the solo Bach Sonatas and Partitas that will remain with the student for the rest of their musical lives. On this note, Brian suggests that we should consider introducing our students to solo Bach via the last movement of the E Major Partita, as it is the most accessible to the developing violinist.

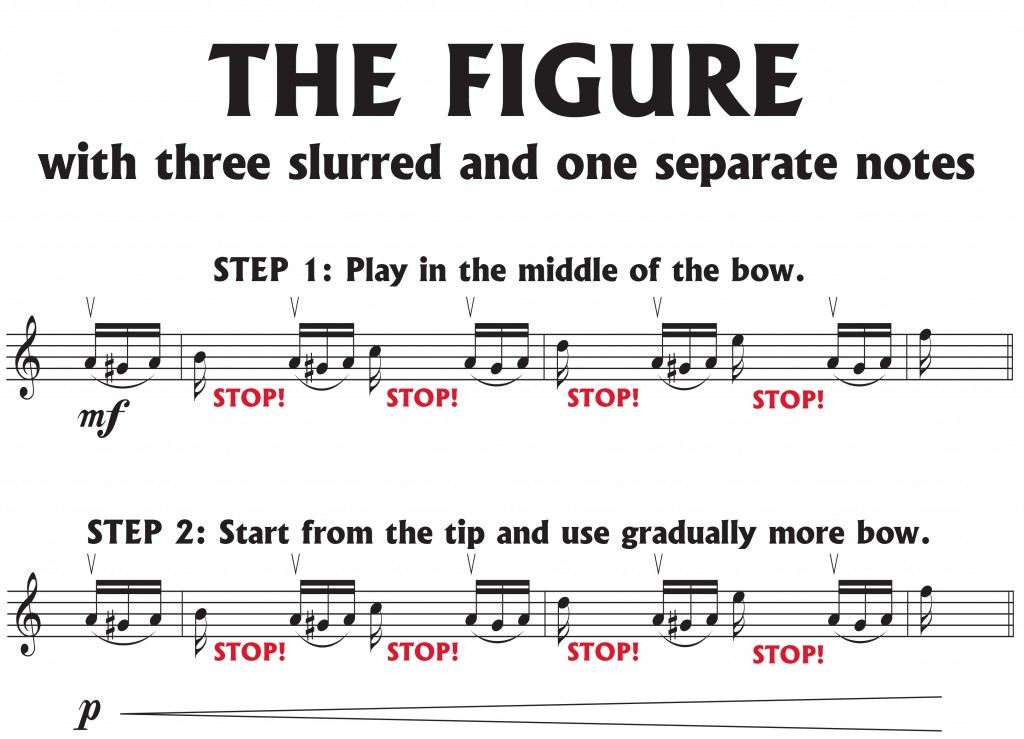

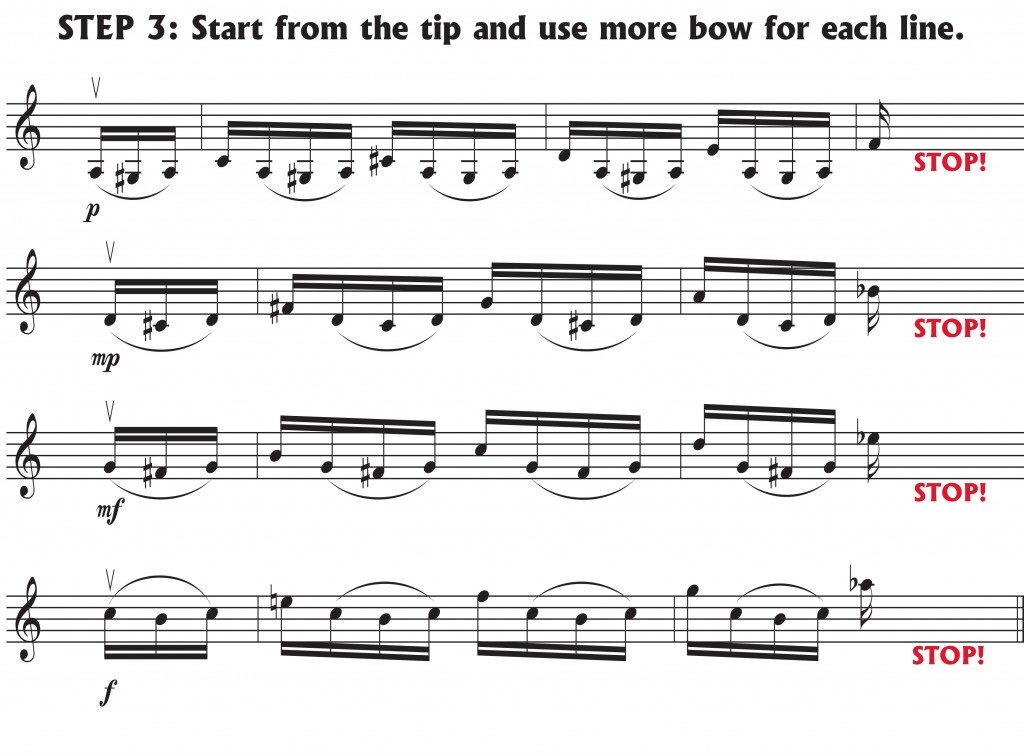

Once the first movement of the Bach Concerto in A Minor has been mapped out for patterns, it is easy to see that the first pattern starts in mm. 4-7. By placing a stop after each unique pattern, the patterns become clearer, and after being practiced in this manner for clarity (stop, prepare, play), the stops can eventually be removed to see the progression of entire pattern.

Brian then leads us to understand that by linking smaller patterns together, we can make a bigger, more useful pattern. For example, mm. 126 – 137 contains four smaller patterns that can be linked together to make a bigger pattern sequence that occurs four distinct times.

Each of the smaller and larger patterns have musical connections and consequences. For example, each pattern could be interpreted in a different dynamic range.

Appoggiatura:

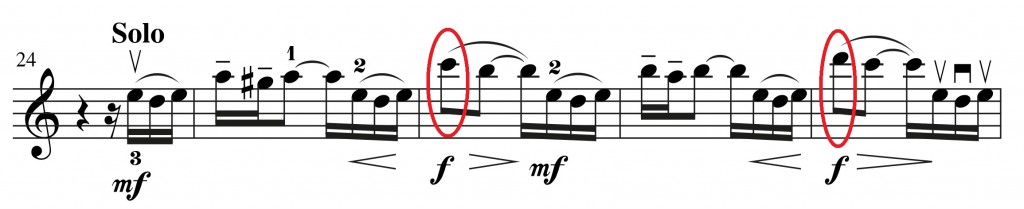

Brian encouraged the teachers to consider that the appoggiatura is an important aesthetic concept that our students must understand fully before they reach the Mozart concertos. The definition of an appoggiatura is ‘a grace note which delays the next note of the melody, taking half or more of its written time value’ (Oxford Dictionary, 2015), and originates from the Italian word appoggiare which mean to lean upon, rest. One of the first uses of the appoggiatura was L’incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppaea), an Italian opera from 1642 written by Claudio Monteverdi. Brian explained that Monteverdi captured the emotional content of the libretto by using the appoggiatura as a tool to depict falling tears. To maintain the falling tear hierarchy, as well as leaning on the non-chord tone, appoggiaturas also frequently employ a diminuendo which highlights the emotional impact further. Bach has written this exact scenario in mm. 26 and 28 in the first movement of the Bach Concerto in A Minor. Here, you can see the implied lean on the appoggiatura, with the diminuendo to the choral note:

Brian encouraged the group to try out the lean and diminuendo on the appoggiatura notes, which helped all the teachers to secure the idea firmly in their minds. In addition, Brian suggested that by reversing the falling appoggiatura notes (and thus neutralising the emotional impact) in mm. 26-28, it becomes easier to understand the immense value of the falling notes to aid the intended emotional impact of the phrase. Brian demonstrated the reversed appoggiatura notes with great affect, as seen in the video below:

Bach Concerto in A Minor – 2nd Movement:

Aesthetic Considerations:

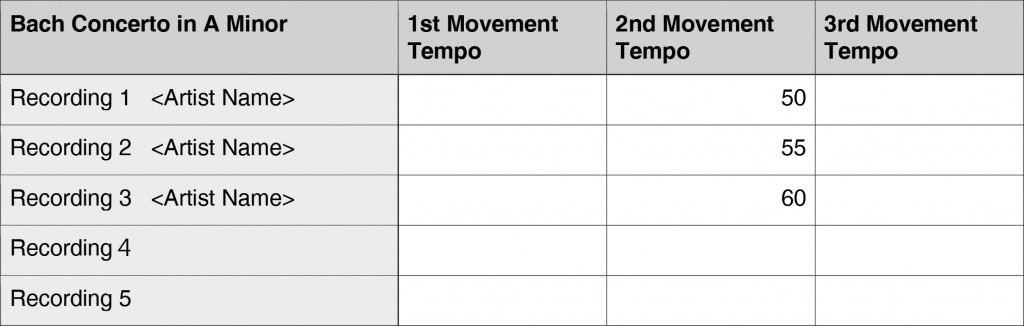

Brian encouraged the group to consider how they guide their students in the aesthetic qualities of the second movement. Aesthetics are the musical considerations of what feels right to us, and teachers have the responsibility to develop these decision making processes in their students. For example, the type of vibrato employed (if employed at all) is an aesthetic choice. Brian suggests that the vibrato in the second movement is relaxed, but not too slow and wide. He considers it a medium vibrato piece, but stresses there are many other suitable choices available to the performer. Tempo is also another important aesthetic choice. Brian asks his students to create a tempo chart for all three movements of the Bach Concerto in A Minor, then tasks his students to research at least three, but preferably five recordings. This also helps foster a productive listening environment amongst students. Once listened to, the student must note down the speed of the recording in order to build up a wider picture of variation between performance tempos. An example table is as follows:

Brian suggests that it is acceptable to play either faster or slower than the researched range, but performers must have the knowledge that they are doing so. The choice of tempo must be an informed choice rather than the choice being because they ‘just feel like it’.

Bach Concerto in A Minor – 3rd Movement:

Gigue Bowing:

The third movement of the Bach Concerto in A Minor is a dance, and we must feel the dance in our bodies and play it as such! Brian guided us through some activities we could try with our students. First, we must find our dominant foot and hop on it whilst we play. It is a difficult activity to achieve, but it helps the performer to feel where the dance is within the music. Another good piece to work with on this bowing and dance feel is the Gigue by Veracini, which can easily be worked on as a review piece for this level of student.

Bariolage:

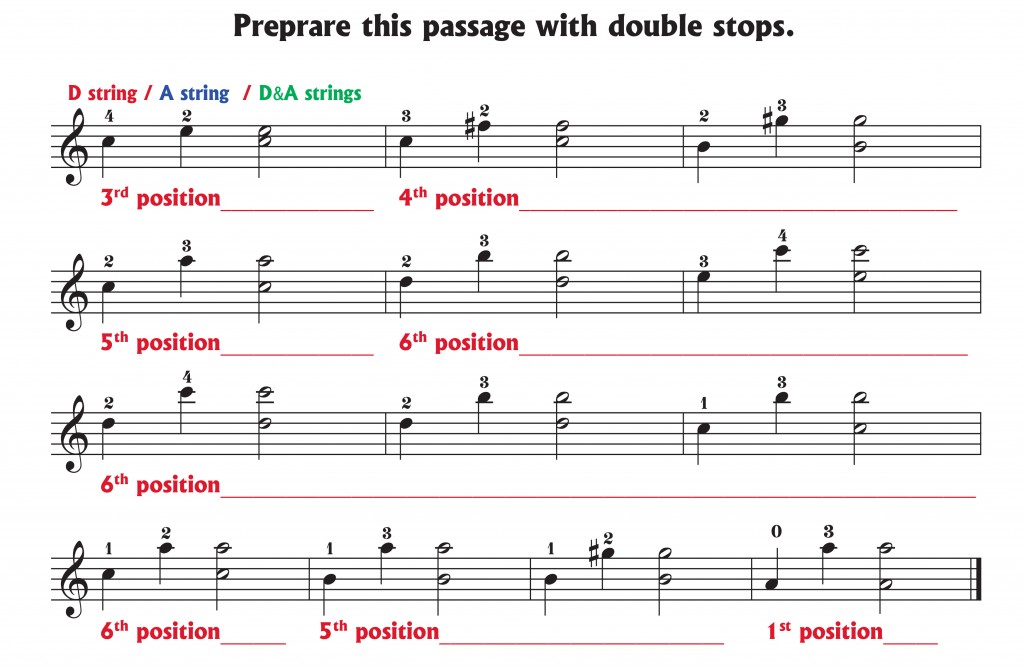

Brian reminded us that the bariolage section in the third movement can cause significant problems for students, and must be mapped out carefully in advance.

Bariolage is a string crossing technique that involves an open string, and the student must be very conscious of their elbow position in order to maintain a consistency of sound over the strings.

If you consider that each string has three arm level positions, for example A1 (near D), A2 (middle), A3 (near E), then there are twelve possible arm level positions on the violin. As teachers, we will need to guide the student carefully in sections such as mm. 105 – 117 to make sure the bow is not too right side orientated, otherwise the E’s will dominate the Sound.

This however, does not need to be addressed during the first stage of learning, as this type of clarity can be refined at a stage of development where the piece is being polished.

Final Thoughts:

Brian finished the Bach Concerto in A Minor masterclass by stressing that our job as teachers is to empower our students to be the very best they can be, and as teachers, we must aim to remove any limitations we see surrounding the progress of our students. He also suggested that we plant the seeds of Bach here with the Concerto in A Minor, which will last our students for the rest of their lives. Therefore, important work must be invested here to sustain the development of the student in years to come.

For more information on the teaching of Dorothy DeLay, an excellent starting point would be ‘Teaching Genius – Dorothy DeLay and the Making of a Musician’ (Sand, 2005).

References

Oxford Dictionary (2015). Available at: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/appoggiatura [Accessed 1 Dec 2015].

Sand, B. (2005) Teaching Genius – Dorothy DeLay and the Making of a Musician. New Jersey, USA: Amadeus Press.

*****************************************************************************

Helen Hines

Studio Director of ‘Violin with Helen’ in Reading, United Kingdom

Education

Helen holds an MA in Instrumental Teaching from the University of Reading (where she graduated with distinction), and violin teaching diplomas from Trinity College London (ATCL), and the Associated Board of Royal Schools of Music (DipABRSM).

Website

www.violinwithhelen.co.uk

*****************************************************************************

8th European Suzuki Teachers Exchange Convention in Germany

28 – 31 October 2016

We hope to meet you all again for next year’s Conference, and extend an invitation to all violin, viola and cello teacher of the worldwide Suzuki community.EVERY Suzuki teacher

and interested string teacher

is very WELCOME!